Dear advocates and adversaries of the Oxford comma, it is with humility, sadness, and relief that I inform you that you are both wrong. Now that I have alienated both sides, I will explain, but first, let’s make sure we are all on the same playing field.

If you are the rare breed that may be reading this without knowing the definition, the Oxford comma, also called the serial comma, is a comma that precedes the last element in a series (before the conjunction “and” or “or”). For example:

With the Oxford comma: Dan is cunning, witty, and wise.

Without the Oxford comma: Dan is cunning, witty and wise.

There are a plethora of pundits for and against this powerful piece of punctation. These advocates and adversaries are equally determined, derisive and disdainful. And they relish their respective resolutions and repartee. But let’s save alliteration for another day.

The Oxford comma advocates will tell you that their special friend prevents ambiguity, promotes clarity, enhances the comprehension of items in a list, creates the appropriate pause, and only takes a fraction of second to add. It is tradition. I mean, it comes from Oxford, my dear. They are lovely people, but a wee bit elitist.

The adversaries will warn you that this comma is silly, unnecessary, wastes time and space, insults the readers, and creates a redundancy – the comma and the conjunction serve the same purpose. They even have a slogan they have bandied around since 3rd grade, “when in doubt, leave it out.” To be fair, they can sometimes be as pretentious as their rivals when they point out that the Associated Press Style Book does not require the Oxford Comma.

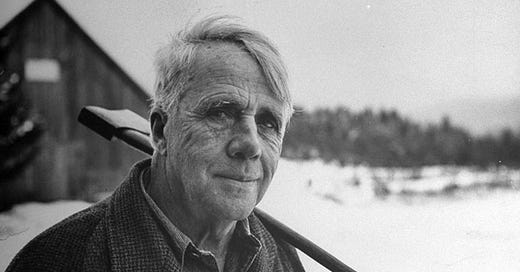

So, it is with kindness, tact and diplomacy that I will end this debate. In fact, it has been over for a long time. In 1922, Robert Frost wrote the indelible poem, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” [1] Within the poem he penned the powerful first line of the last stanza without an Oxford comma:

"The woods are lovely, dark and deep,"

Without Robert Frost’s permission, at some point of production, an editor or typesetter added an Oxford comma, temporarily making it:

"The woods are lovely, dark, and deep,"

Frost soon became aware and had it stricken once again. He made that decision swiftly, deliberately and consciously. Frost realized what too many elitist grammar nerds have forgotten or maybe never knew – that the point of words, grammar, and punctuation are to convey meaning. He was not providing a simple list about three different characteristics of the woods; he was telling us the woods are lovely because they are dark and deep. That image evokes such a profound mystery around stopping by the woods. Why did the man stop? What does he mean when he tells us he has miles to go before he sleeps? Was he really talking about sleep? I won’t analyze the entire poem here. Easy enough to search that. But what is indisputable is that the author made an educated decision to convey meaning.

If that example is too literary, then consider this simple example:

With the Oxford comma: I love my dogs, Madison, and Hunter (Madison and Hunter walk my dogs)

Without the Oxford comma: I love my dogs, Madison and Hunter (Madison and Hunter are my dogs)

Both of these versions can be correct as long as they are conveying the intended meaning. And that is precisely why, as Frost and my dogs elucidate, to be unequivocally for or against the Oxford comma is quite simply wrong, tiresome, and silly. It depends.

On a final note, if you remain unconvinced, let’s go to the source. If we really want to learn the fate of the Oxford comma, then maybe we should go to the Oxford English Dictionary for a definition:

“Oxford comma, n. A comma immediately preceding the conjunction in a list of items.” [2]

The definition is clear in what it does and does not say. “A” comma. The word “a” is an indefinite article. The word “the” is a definitive article. Indefinite is vague and unspecific, while the definitive is specific and particular. If Oxford wanted to tell us that there is a specific, consistent and regular comma preceding the conjunction, then it would have referred to “the” comma that resides there. Moreover, Oxford does not demand or even insinuate that it is a required punctuation. They are simply telling us that when you use “a” comma here, it is called the Oxford comma. Maybe it would help if we changed its name to the “Optional comma.”

Case closed.

And now we can turn to a much more serious discussion – the use of the first comma in a list. This comma doesn’t even get the respect of a name. So, I have decided to call it the Stoneking comma. Consider the following:

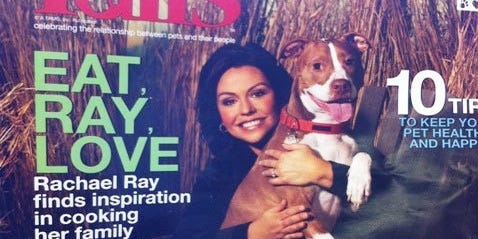

"Rachael Ray finds inspiration in cooking her family and her dog."

Yikes. This television chef has become a murderer and presumably a cannibal. If you only add the Oxford/Optional comma, she is still cooking her poor family and the rest of the sentence does not make much sense:

"Rachael Ray finds inspiration in cooking her family, and her dog."

Only the Stoneking comma saves the day. We are clear that she finds inspiration in each of these three things separately:

"Rachael Ray finds inspiration in cooking, her family, and her dog."

You are more than welcome.

Now I must go feed the dog, do the dishes and [Optional comma here or not] take a nap.

This piece is funny and makes my day! THANK YOU for setting the record straight!

I was just being sassy…:). I think we need to find a Travis comma. Maybe those are the ones that set off dates???